How written Chinese works

The Chinese writing system has now been in use for over 3,500 years. Its origins lie even deeper in the past. It is the oldest writing system in use and one of the most widely used. In fact, until the 18th century, more than half of the world’s books were written in Chinese.

The basic principles behind Chinese characters have remained unchanged for thousands of years.

Chinese writing principles

Chinese writing is mainly logosyllabic (or semanto-phonetic). This means written Chinese is not based on a phonographic system (such as the Western alphabet, in which letters only represent sounds).

In written Chinese, each character represents a morpheme (unit of meaning).

That may either be:

- a physical object

- an abstract notion

- or a pronunciation marker.

Characters, morphemes and syllables

In oral Chinese, each character or morpheme is actually equivalent to a syllable.

However, Chinese only has a limited number of syllables, even when tonal distinctions are taken into account. This results in a great many homophones (morphemes with the same pronunciation but totally unrelated meanings). For example, there are 188 different words or morphemes expressed by the single syllable /yi/.

As you can imagine, in written Chinese, this could create a lot of ambiguity.

Fortunately, around 200 BC, a a solution was found to help distinguish between two words with the same sound that were also represented by the same graph: add another graph to carry the new, specific meaning.

From this, in 120 AD Xu Shen compiled the Shuowen Jiezi, defining the six basic principles used to create characters in Chinese writing.

The six principles of Chinese writing

The first two are quite straightforward:

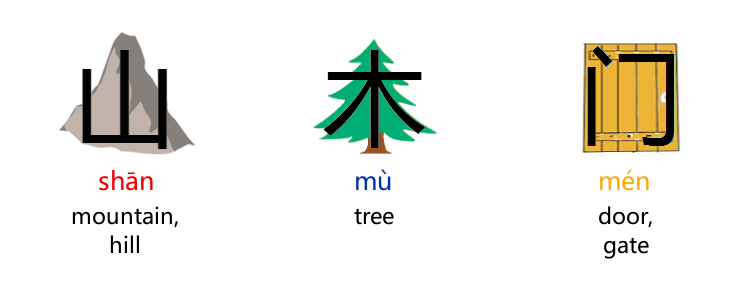

1) Pictograph

The character is a graphical depiction.

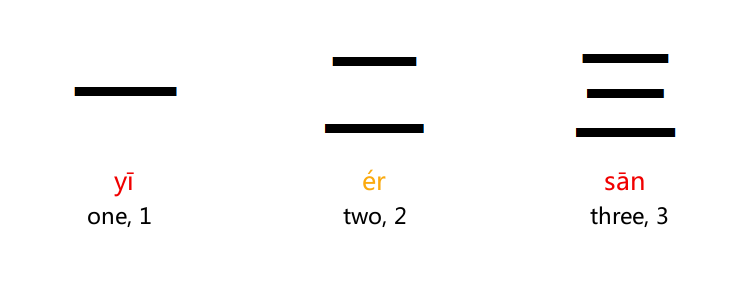

2) Ideographs

The character represents an abstract notion.

Next come different combinations of visual elements.

3) Logical aggregates

Several parts are combined to create new meaning. By example, to express ‘take a rest’:

4) Phonetic complexes

One of the parts is a character used for its phonetic value. The other, often called radical, is a kind of ‘add-on’, a graphical component that indicates the general topic of the character. These two categories cover more than 75% of characters in Chinese writing.

Radicals are traditionally used in print dictionaries as a way to sort and group characters. However, despite a canon of 214 radicals established under the emperor Kangxi in 1700, the list is not clearly defined.

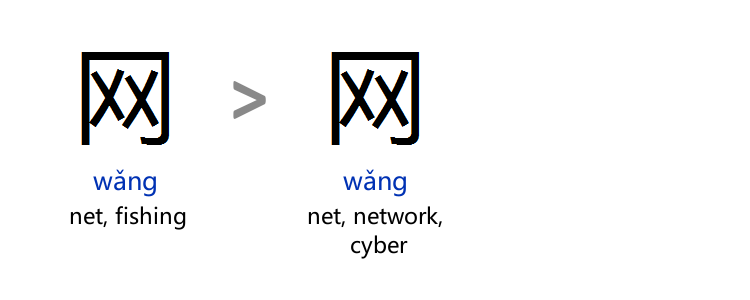

5) Transference

A character, often with a simple, concrete meaning takes on a more abstract meaning.

6) Borrowing

A character is used, either intentionally or accidentally, for some entirely different purpose.

This system of one distinctive character for each morpheme forms the basis of Chinese writing.

Mono- and polysyllabic words

Because each morpheme carries a single, distinctive, inherent meaning, many Chinese words are monosyllabic (which is not the case in English, where it often takes more than one morpheme or syllable to make a whole word).

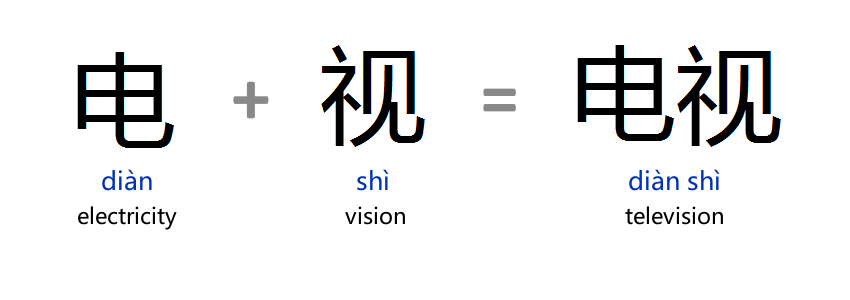

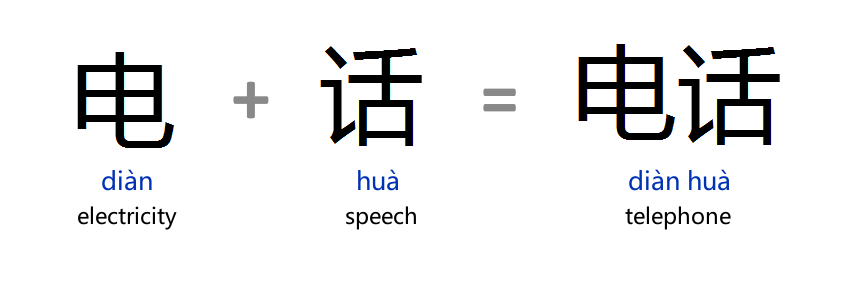

But polysyllabic words also exist in Chinese, also based on morpheme combinations.

Sources

Britannica — CJVLANG — Wikipedia — Ancient Scripts — Ancient China — Omniglot